Yukina meets us at the south entrance of Hiroshima railway station on a hot night in late July. She is taking us to a nearby multistorey building where the fifth floor is dedicated to a dozen or so small concessions serving Okonomiyaki. We’re served by Kyo Tanaka, a slim, smiling magician who slices, dices, fries and combines wafer thin crepes, cabbage slivers, seafood, egg and soba noodles into a rotund pancake topped with spring greens and a pork-infused brown sauce. Washed down with the local lager, it’s a heavenly dish.

Yukina is a former student of my daughter, Lucy, who, until recently, taught English as a second language at Discover English in Melbourne. A slim, attractive 20-something year old, Yukina has dark hair with blonde ends and fabulous fingernail art. She’s fun and funny. During dinner she brings us up to speed on Japanese politics, life in Hiroshima and her recent application for a working visa back in Australia.

We share our plans to visit the Hiroshima Peace Park the next day and she advises us to book tickets beforehand for the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum (within the park) to avoid queuing longer than necessary. Hiroshima is hot in late July – it’s about 35 Celsius when we arrive at 11.30 am – so locals are ultra sun smart in hats, long gloves and shielded by umbrellas. Tourists tend to stand out by being underdressed, hatless and red-faced.

Thanks to Yukina’s suggestion we’re able to enter the museum immediately after arriving at the Peace Park. It’s already crowded, but most visitors are suitably solemn and move around the exhibition in an orderly fashion.

The main exhibition focusses on the dropping of the Atomic Bomb on 6 August 1945. It takes us about 90 minutes view the photographs, fragments of clothing, notebooks, fused bottles, twisted metal and broken pieces of everyday life on display. Afterwards we talk about our feelings about what happened and the museum’s portrayal of the bombing and the aftermath. It’s easy to say, ‘words fail’, but the magnitude of this destruction is difficult to understand or convey. Above all, for me, the individual stories and items owned by survivors or victims’ families have humanised an event that is more often characterised by numbers: an 3-metre, 4 -ton bomb, detonated at 600 metres, 80,000 killed instantly, 300,000 total deaths, including 14,000 missing, a 2-kilometre radius of immediate destruction. But the exhibition introduces us to Masako, a 13-year-old school girl, Jiro, a 31-year old railway worker, and Chieno, his 26-year-old wife. It reminds us, too, that when disaster hits, all that most of us feel the need to do is to find and protect family. And when we are full of fear, it’s our mother’s name we’re likely to call.

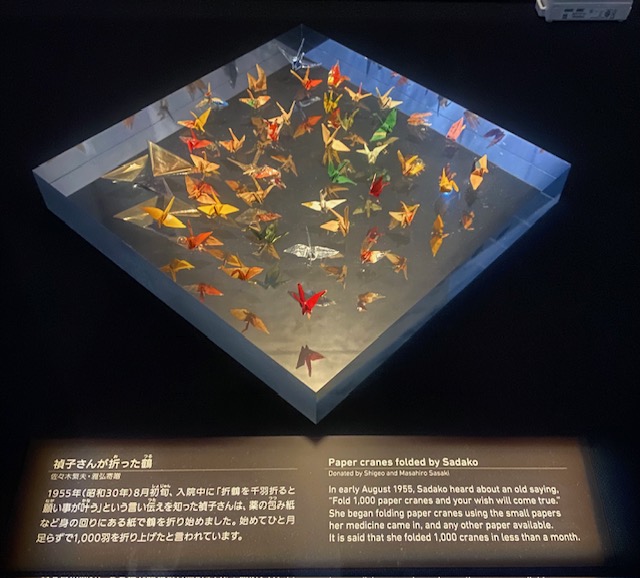

We also learn the story of Sadako Sasaki who was two years old when Hiroshima was bombed. At age 11 she developed leukaemia and started folding paper cranes from the papers in which her medicines were wrapped. She was hoping to fold 1000 as this would bring good luck, but she did not reach her total. Her classmates finished the task after her death and created the momentum to establish the Children’s Peace Monument, or Tower of a Thousand Cranes, in the Peace Gardens. The monument was designed to ‘comfort her soul and express desire for peace’.

So many stories of love, loss and grief. Family members lost, found or missing forever. People without shoes, walking on burned feet, through fiery rubble, to find those they loved.

There’s another gallery we need to visit. For last night Yukina told us of her grandmother, Emiko Okada, who shared her living history in 2001 in the form of a video for the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

She was one of hundreds of hibakusha (A-bomb survivors) who has done so. We search her name, locate her 20-minute recording, and seat ourselves in front of the screen to watch this gentle, elegant, articulate older lady tell her story.

On 6 August 1945 her older sister had called out, ‘see you’ as she left the house for her school. Her father, a teacher, headed to a demolition site. The locals were selectively demolishing houses in preparation f or expected bombing raids as the US army advanced further from the southern islands of Japan.

As the B-29 bomber, Enola Gay, flew overhead, Emiko’s two younger brothers ran outside to see the plane, and she followed them. Light flashed and she lost consciousness. When she came to, her badly burned brothers were being bandaged by her mother, who was bleeding from gashes from flying glass. Most of their home was destroyed.

It took two days before they were finally reunited with her father. Her parents then spent weeks searching for her sister who has never been found. Emiko’s voice wavers as she says she still feels and shares her parents pain and grief at this loss.

As a visitor, it’s very difficult to make any sense of the destruction of this city on that sunny day in August 80 years ago. My own father served with the RAAF in Moratai and Borneo. My mother had volunteered and was due to officially join the women’s services on her 18th birthday on 16 August 1945, but peace was declared a few days before. Both my parents believed that the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki was the circuit breaker that brought hostilities in the Pacific to an end.

But in the museum we learn that at no time was the imminent use of this scale of force revealed. That the Japanese government was requested to surrender but were given no warning whatsoever that civilians would be the targets within days if they did not sign.

I don’t pretend to understand much about this situation at all. But I do understand that there is nothing defensible when it comes to killing civilians be it in Hiroshima, Srebrenica, Kiev, or Gaza. And the quiet words of Yukina’s grandmother are a compelling reminder of this fact.

We travel for many reasons.

Perhaps the most important is to listen and learn. In Hiroshima, this is in the hope we will hear Emiko’s words that this must never happen again.

First published in Wild & Inspired, ASTW, 2025.